welcome back to dehydration stations— my series on experimental hiking meals (a little detour from my usual baking adventures in penny’s kitchen!).

not interested in this series? you can unsubscribe from just dehydration stations by following the steps here. and don’t worry! the baking updates continue as normal on penny’s kitchen

over the years i have iterated ever closer to my ‘optimal’ meal plan for hiking. it’s a delicate balance of a number of interrelated factors:

total energy needed

macronutrients (protein, fats, and carbs)

cost

weight

cooking requirements

ease of purchase

other nutritional considerations like fibre, and electrolytes like sodium and potassium to prevent cramping

weather (no one wants cold dinner in the rain!)

i thought for this post i’d start way back at the beginning - how much food do i need anyway?

how many calories do i need on a hike?

i assume most readers will be familiar with the calorie, the measure of energy. the amount of food you eat and the amount of energy you burn on a hike can both be measured in calories (technically kilocalories, but no one calls them that!)

when planning a hike, you would generally want to match the two up, so you take exactly as much food as you need - this requires knowing, or approximating, how many calories you will burn on the hike

many of us now wear fitness watches on a daily basis that will tell you how many calories you burnt (past tense) on a given day, and doing a given exercise. for hiking planning, the real trick is to forecast your future caloric burn over a day, a weekend, a week, or more!

the role of the rmr

here’s how we start:

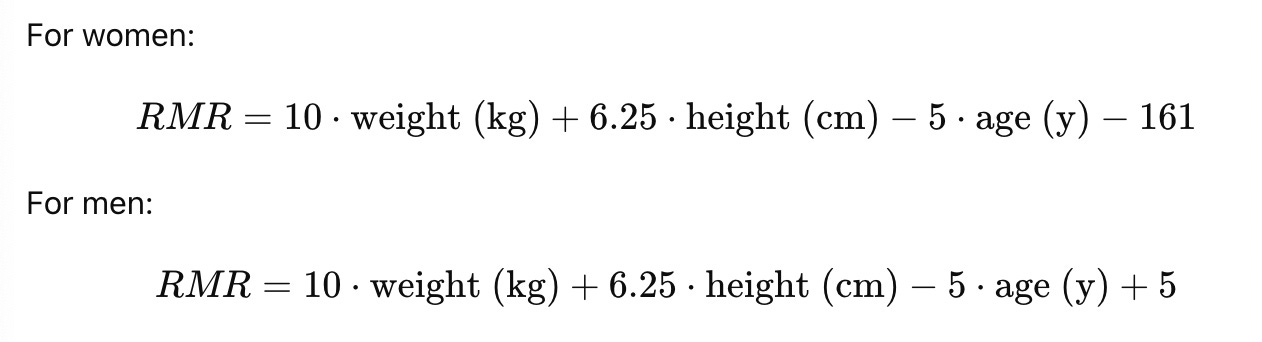

the mifflin st jeor equation predicts the total energy burn of a person at rest (what we call the RMR (resting metabolic rate)

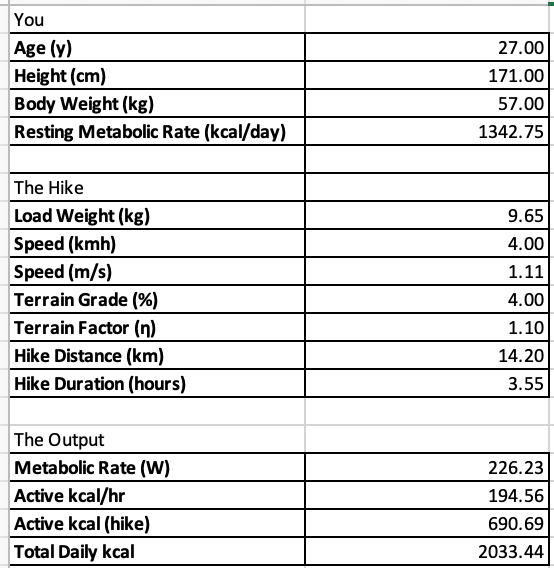

for me, this spits out 1342 calories per day. this equation was derived in 1990 by measuring the oxygen intake and carbon dioxide exhalation of 498 healthy adults and then applying multiple linear regressions to find the best-fit predictors of RMR using the easily-measured variables of height, weight, age and sex. it’s still the gold standard approximation today.

sidebar: there are other equations you can use, such as the harris-benedict, owen, cunningham (uses body fat percentage), henry, and katch-mcardle. for me these all give very similar results so i tend to use the mifflin st jeor as my baseline.

this number is the base energy i would burn to maintain basic life functions at rest: breathing, keeping my heart beating, and so on. note this figure is always the same, irrespective of the hike you are planning, the weight of your pack, etc.

any energy burnt while moving (i.e. hiking) is added on top of the RMR to get the total energy requirements for each day (TDEE).

using the pandolf equation

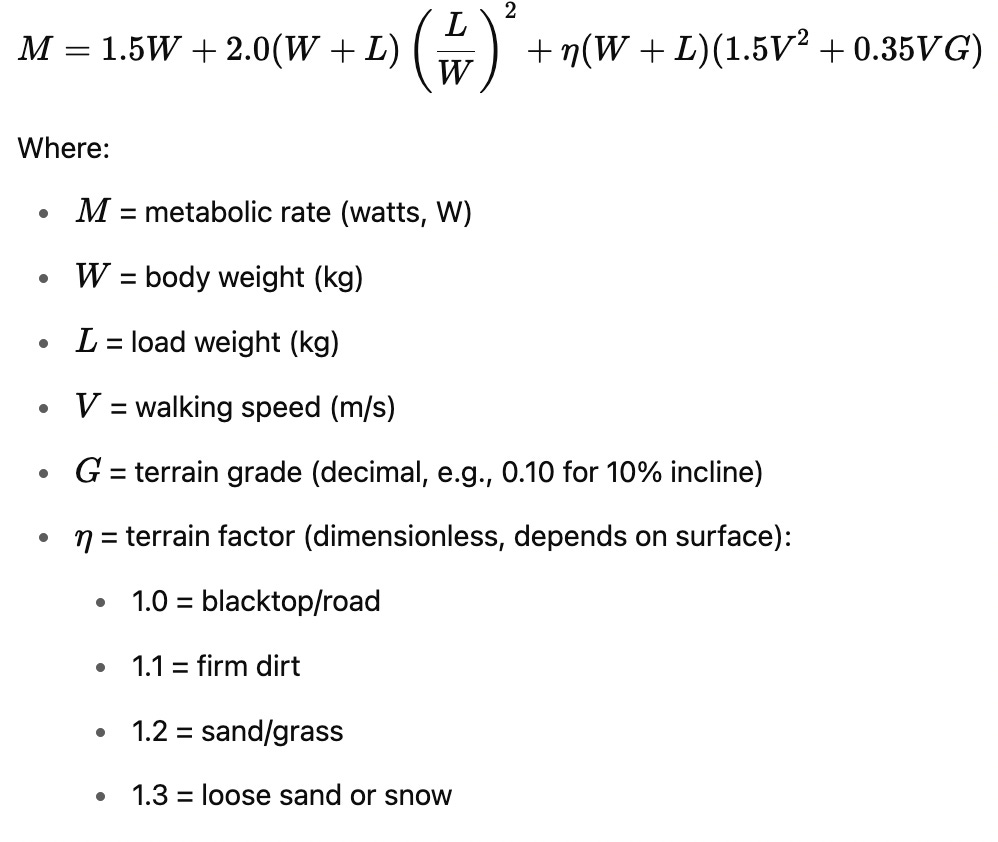

the Pandolf equation is used to estimate the metabolic rate (energy cost) of walking while carrying a load, accounting for body weight, load weight, walking speed, and terrain slope.

it was developed in the 1970s as part of US Army research to assist with mission planning. i add on a layer of complexity, adding in the hike distance (km) which then gives me the hike duration (hr) and total kcal burnt for the hike.

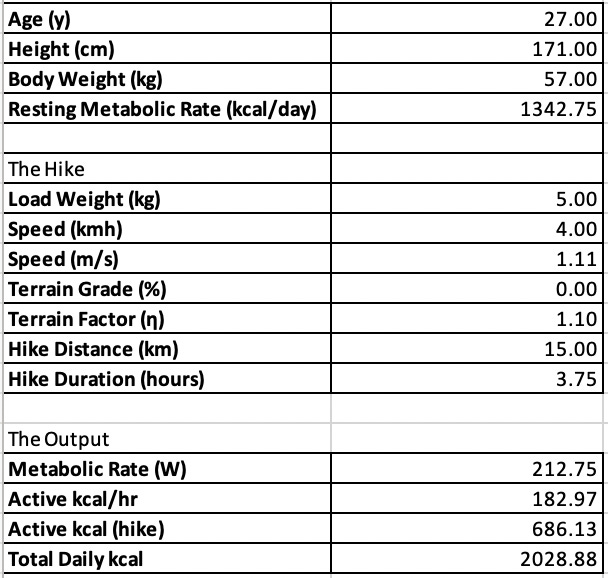

as an example, say i am planning a day hike that’s 15km, 0 elevation gain (so 0 gradient). i know from experience i tend to walk at 4kmh, and my day pack will weigh around 5kg.

plugging these numbers into my planning excel sheet gives us a metabolic rate (M) of 212W, which equates to 182 calories/hour or 686 calories for the whole hike. at the bottom you’ll also see my total daily calorie burn for this hypothetical day of 2028 calories.

this equation is pretty good, but any hike with significantly different elevation gain and loss can get a little tricky. for any hike with a significantly different climb and drop i will split up the hike into uphill and downhill sections and add together the results.

we now have a total number of calories required for this day of hiking - which is exactly what i need to pack, right?

not so fast

the pack weight puzzle

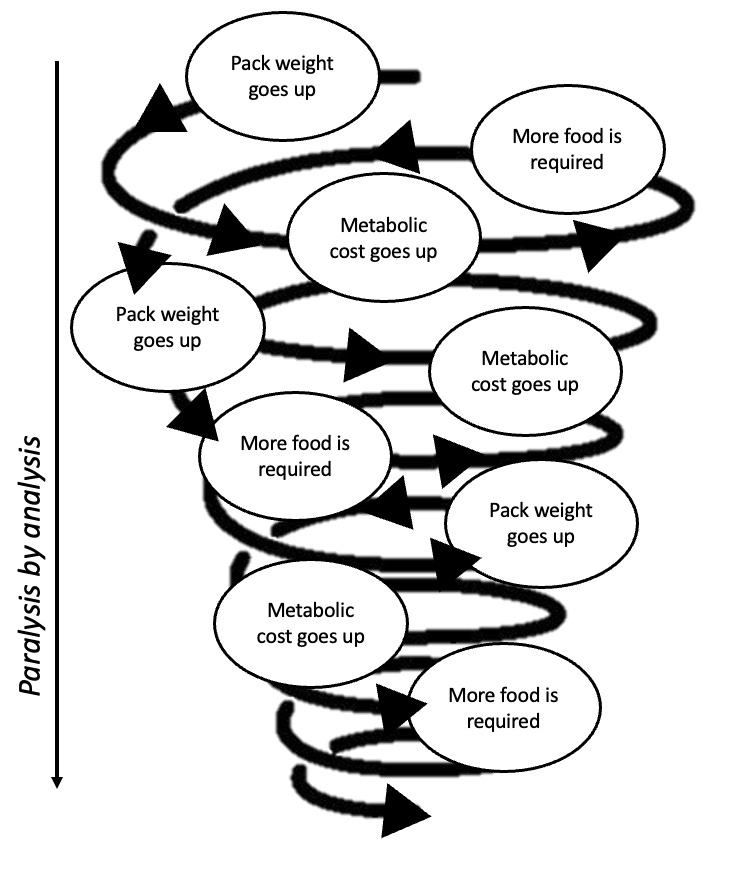

you’ll notice pack weight is a variable in the Pandolf equation, but the weight of your pack includes the weight of the food you’ll carry, which depends on how much energy you need, which depends on the pack weight, which depends…

this isn’t a huge deal on a day hike but can quickly become overwhelming on a multi-day hike where the weight of your food can be many kilos and the pack weight has a real impact on how fast you walk. and don’t forget - each day you eat a day’s worth of food so the pack weight is also reducing each day. so what do you put?

caloric density of food

this is where i find the problem gets really interesting. the food weight also depends on what you bring - 2,000 calories of peanut butter weighs a lot less than 2,000 calories of bananas (318g vs 2,280g for anyone playing at home).

the lightest possible 2,000 calories would be pure oil at 9 cal/g for a total of 220g.

a typical hiker diet (oats, trail mix, wraps, dehydrated dinner) might clock in at 660g for 2,000 calories.

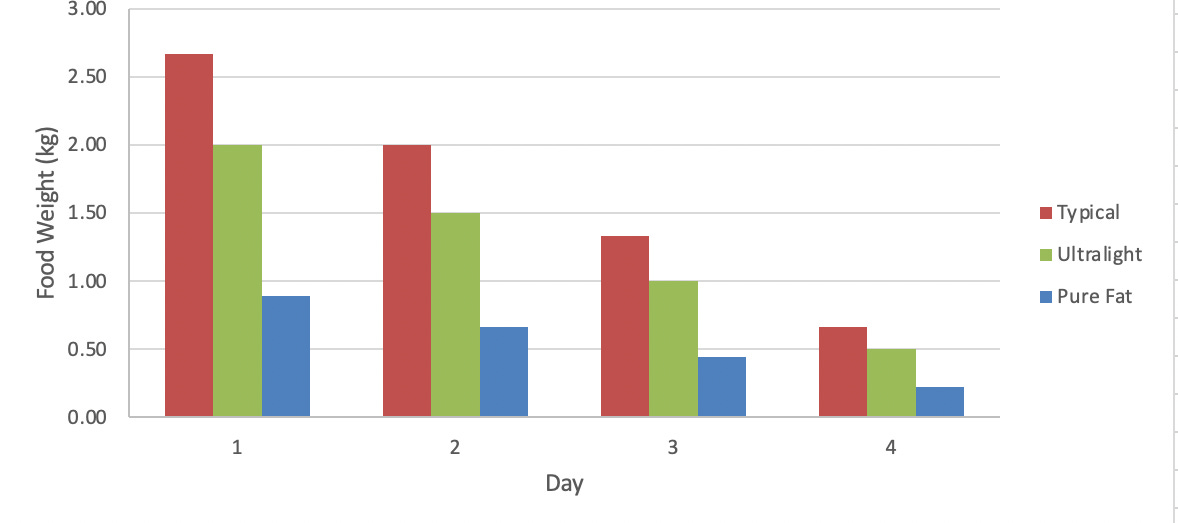

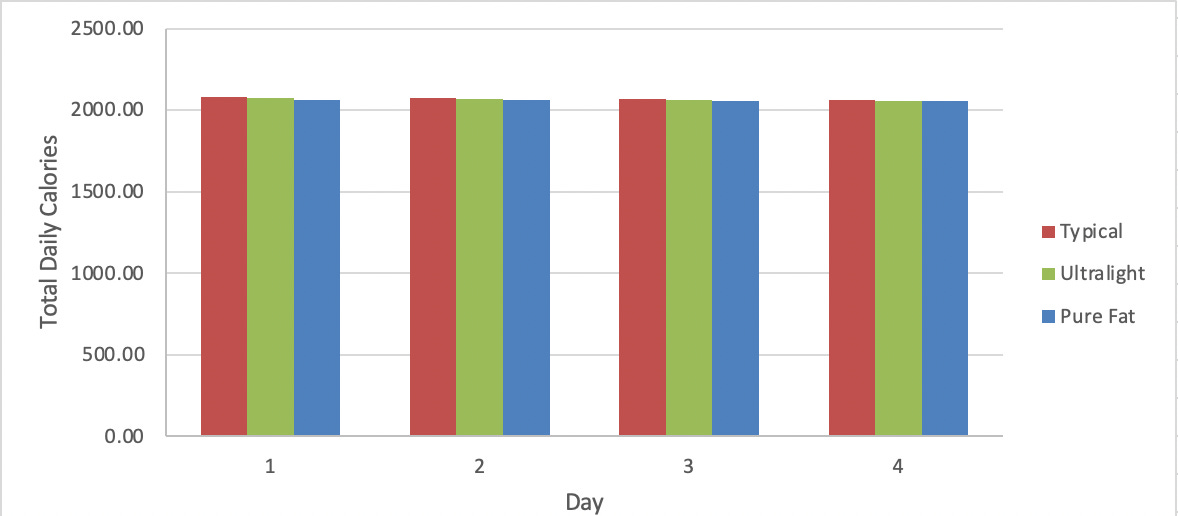

over the course of four days, the pack weight would change dramatically as shown above - but does it matter for your caloric burn planning?

i’ve done the maths here and turns out it’s not too much of a difference overall (about 8cal/day or 1 almond)

the caloric burn barely changes across each day as the pack weight goes down

so for planning purposes, i will use the same load weight for each day’s calculations and allow about 550g per day of food (knowing i tend to pack slightly more ultralight food selections that the average hiker, and this we will get into later!)

multi-day adventures

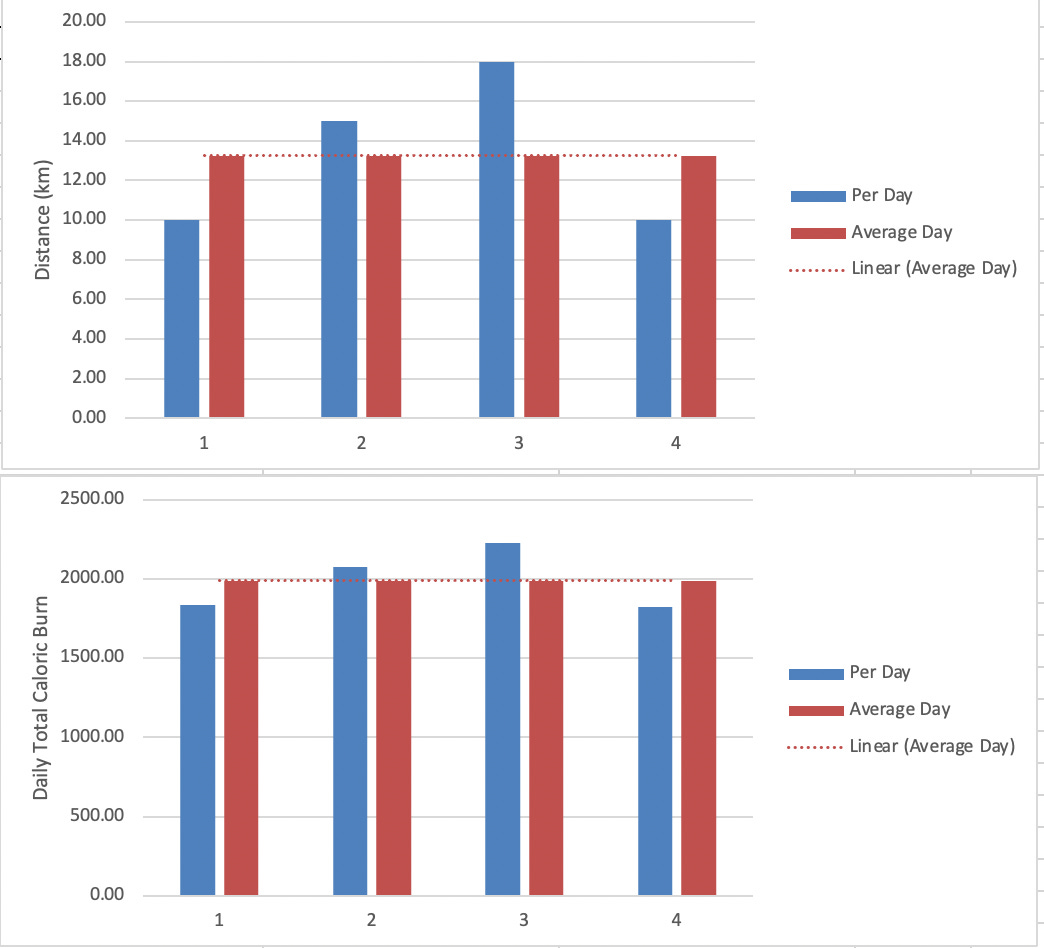

now - what about multi-day adventures?

do you calculate each day individually and take the average? or do you take the average distance and gradient of each day walking?

once again i have done the modelling for you and it doesn’t matter! at least for our total daily caloric burn purposes. so i would divide your entire hike distance and elevation by the days to model the ‘average day’ and use this to plan your requirements

the total

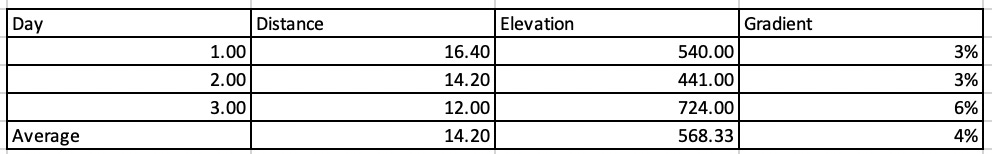

so let’s bring it all together with a hypothetical hike - say we are doing the falls-hotham alpine crossing in victoria, australia over 3 days

i would use 14.2km for the distance, 4% for the gradient, and 3*550g+8kg for the pack weight

so, we’ve crunched the numbers and landed on a target of roughly 2,033 calories per day. that’s our starting line — but the real magic (and challenge) lies in deciding what those 2,033 calories look like.

in the next post, i’ll open my hiking pantry and share how i build a day’s worth of trail meals that balance calories, weight, nutrition, and (of course) flavour